Response To A Toxic Political Climate? Art About Parasites

Toxoplasmosis infects 30 to 50 percent of the world’s population, but its effect on human beings isn’t fully understood.

It’s commonly passed from cats to humans through the litter box, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said people are more likely to get it from gardening or eating raw meat than from their pet. Rats infected with the disease will no longer fear cats—and they may even be attracted to them.

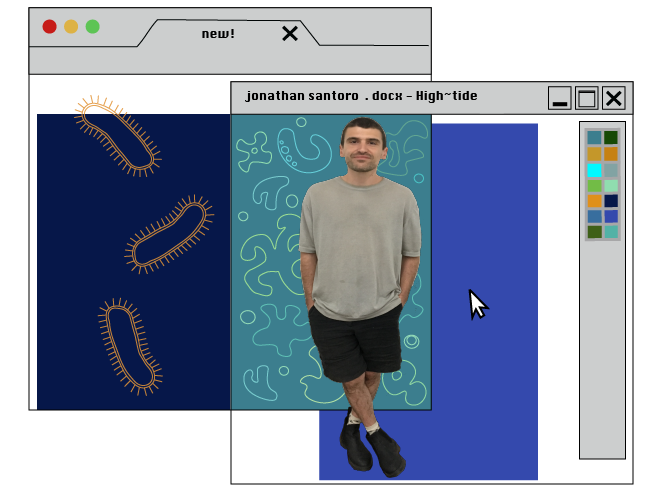

And it is the namesake of Jonathan Santoro’s recent artwork, which is currently being featured at the High Tide Gallery in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia.

Artist Jonathan Santoro/image by Julia Bell

In the face of the proposed elimination of the National Endowment for the Arts under the Trump administration, creating art today can sometimes be in conflict with and in response to an anxious political environment.

Santoro said he does not identify as a political artist, but politics have seeped—almost by newswire-transmitted osmosis—into his work on this occasion. He cites the March for Science, the polarization of social media, and the close of Obama’s presidency as inspiration for his most recent work.

“I don’t think a young artist can make art that looks good above a couch these days and feel satisfied with themselves,” Santoro said, explaining the recent shift.

In fact, his most recent artwork could not physically hang on a wall. His pieces in the “Toxoplasmosis” exhibit, made in collaboration with two other artists, Michael Assif and R.Lord, include plastic castings of household objects and a crafted chair with carved detail.

Santoro was never formally trained in the arts; he is more likely to construct a wall than hang an MFA on it. He studied Art History in college and then made a living in Philadelphia by taking fabrication jobs. His fabrication background and his blue-collar work, which developed his hand skills, is evident in his pieces, which are generally casted, molded or woodworked.

The High Tide gallery is tucked into the second floor of an industrial-looking building. In the back, there’s a hidden studio space behind an inconspicuous door cut out of a wall. In contrast to the stark angularity of the gallery, the studio is cluttered with artwork and supplies on every available surface.

One piece in the exhibit, a urethane plastic cast, was molded to resemble a cat struggling under a black Hefty bag. The work is a nod to Schrödinger’s cat experiment—where a cat could be both alive and dead simultaneously—and the disregard of facts in the current political climate. In this vein, Santoro was inspired by the Wall Street Journal’s Red Feed, Blue Feed experiment on the political disparities between social media newsfeeds.

“Where we wanted to go with the show, or at least my contribution to it,” Santoro said, “is thinking about a social media feed where you’ll scroll through Facebook—no matter what politics you have— and there’s a common denominator of kind of horrific, attention-grabbing headlines.”

In Santoro’s estimation, the current political climate has led art to become more responsive to cultural and political topics, and less relegated to abstract discussions in lecture halls. That perceived shift, Santoro thinks, could have younger people experiencing more anxiety about what’s ahead.

“I think people of millennials and younger are starting to feel there’s not a designed future for them,” Santoro said. “There’s not the house and the kids and the car and all this other stuff.”

Orkan Telhan, an artist and associate professor of Fine Arts in the School of Design at the University of Pennsylvania, agreed the political climate of uncertainty contributes to a shift toward more political art.

“They are worried about the future,” he said, echoing Santoro’s sentiment. “They are worried about the climate, they are worried about the education system. Human rights are now at stake.”

In Telhan’s view, art can ask questions of politics—“Where is the power struggle? What are the stakes?”—more deftly than news media. His previous work has included exhibits on social injustice in Detroit, questioning inherent prejudices, and civic engagement.

“If you read about these issues in the newspaper, you see them and you forget about them,” he said. “But if it turns into a more powerful artistic experience, it sticks in you much longer.”

However, Ken Lum, the Chair of the Fine Arts department at the University of Pennsylvania, was skeptical of political art because of its lack of efficacy.

“Many people see contemporary art, no matter how political the action or the gesture may be, as highly compromised,” Lum said. “Because it’s in a system that doesn’t try to break out of art and into the realm of the real.”

Regardless of one’s stance on the value of politically-inspired artwork, it has become a lightning rod for controversy with recent disputes over a Trump-inspired production of “Julius Caesar” and a Kathy Griffin photoshoot.

“I think there was a lot of apathy in the years of Obama,” Santoro said. “But today you kind of have to chose a side.”

The exhibit “Toxoplasmosis” remains at the High Tide Gallery through July 15.

Listen to an interview with Jonathan Santoro

Images courtesy of Jonathan Santoro

We are finding, coaching and training public media’s next generation. This #nextgenradio project is created in partnership with WHYY-FM Philadelphia. Learn more about Next Generation Radio and upcoming programs.